This is the third of six parts of the special report Unfinished Business: Suffering and sickness in the endless wake of Agent Orange.

By Connie Schultz, with photographs by Nick Ut

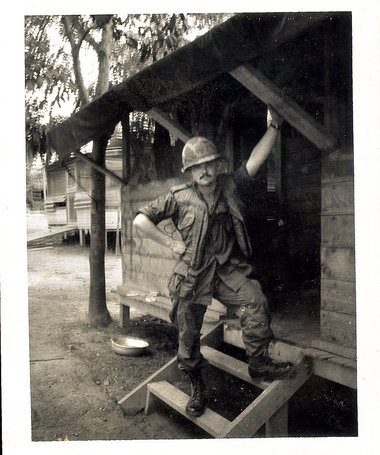

Bill Morris left for Vietnam in 1968, full of American patriotism and a sense of duty. He never stopped loving his country, but he never forgave the U.S. government for his exposure to Agent Orange, and what he was certain it did to his only daughter. Courtesy of Heather Bowser.

Barely 48 hours earlier, Heather Bowser raised her seat back to the upright position and braced to land in the home of her father’s demons.

As the plane descended toward Hanoi’s Noi Bai International Airport, her anxiety soared. The 38-year-old Ohio native had been planning this trip for a long time, but now that she was nearly there, uncertainty was beginning to mute the buzz of her initial excitement.

Her mind raced: What will I find there? What will the Vietnamese people think of me? Am I ready for this?

It didn’t help that she’d been wearing her prosthesis for 33 hours straight. No matter how she shifted and stretched in her seat, she couldn’t ease the ache in her right thigh. She was long overdue for a break from the state-of-the-art mechanical limb that relied on suction to stay attached, but an artificial leg isn’t something you can pull off and hoist as carry-on luggage.

To bolster her courage, Heather pulled out a picture of her father from 1967, just before he made the same journey. Back then, William Allen Morris was a 20-year-old newlywed, one of thousands of young Army draftees girding themselves to land in war-torn Vietnam.

Heather closed her eyes and silently talked to her dad:

How did you feel on your first flight to Vietnam?

What were you thinking as you got closer to the ground?

Were you scared?

She would never get those answers.

What she did know was that her father had marched out of the bowels of a black military transport and into the arms of ghosts that would travel with him the rest of his life. On the same day Bill Morris landed, he and his fellow soldiers were ordered to extinguish a raging chemical fire. They fought the toxic flames for several hours, none of them wearing so much as a face mask for protection.

His soldier’s mantra began that night: One day down, 364 to go.

Heather sat up a little straighter in her seat. If her father could fight a foot soldier’s war in the jungles of a divided Vietnam, she could face whatever awaited her now, when the country was united and at peace. She was her father’s daughter, his “Heather the Feather,” and she knew he would be proud of her.

Pride drove Bill Morris, every day of his life.

He was raised to provide for his family, and was always reluctant to admit he ever needed help.

He was a proud father, the kind who believed you never stop championing the kids you brought into the world. He was a proud veteran, who never asked why it was he, and not his high school buddies with college deferments, who had to go to Vietnam.

Bill was a proud American, too. No matter how angry he would later become with his government, he never stopped loving his country.

As for his time in Vietnam, that was a private hell he would not share. Rarely did he talk to family — or anyone else — about his military service.

He did have his moments. Once in a while, in the days when he was still coming home from work at the steel mill and Heather was finally old enough to toss back a few beers with her dad, he would let down his guard. Heather remembers those talks like they happened yesterday. Some memories burn long, and hard.

Father and daughter would be chatting about the daily ups and downs of life, and his mood would suddenly cloud. That’s how Heather knew he never stopped blaming himself for what had happened to his only daughter.

“If I’d only known,” he’d say, shaking his head. “If I’d known this was going to happen to you, I would have moved to Canada. If I’d only known.”

Bill Morris and Sharon Nelson were students at Bliss Business College in Columbus when they met and fell in love in 1966. She graduated; he dropped out.

“He said he could envision the life of an accountant, and it was boring,” Sharon said.

Bill lived in Wintersville, a hiccup of a town near the Pennsylvania and West Virginia borders. He got a job at the Wheeling-Pittsburgh steel mill, but it wasn’t long before the Army came calling. Nine days before he shipped out for Vietnam, on July 22, 1968, he and Sharon were married.

God didn’t make a man friendlier or more gregarious than her husband, Sharon said.

“He was the kind of guy who walked into a room with 100 strangers and came out with 98 friends.” She laughed at the arithmetic. “There’s always a couple. . . ”

In Vietnam, Bill was an Army specialist armorer, maintaining small arms and weaponry. At first, he wrote to Sharon at least once a month and sent along chatty audiocassette tapes, too. His correspondence offered limited comfort to an anxious young wife.

“We didn’t have e-mail and cell phones back then, so you knew by the time you got their mail things could already have changed,” she said. “We were watching the war on television, watching them carry bodies into helicopters, night after night. Everybody knew what could happen. Everybody knew.”

In February 1969, Bill and Sharon spent a week of R&R in Hawaii. Sharon could see that six months in Vietnam had changed her husband.

“Bill went to Vietnam thinking of it as an adventure. Then reality set in. All he wanted to do was stay alive and get home.

“By the time I saw him in Hawaii, he had become very cautious. He kept looking over his shoulder, sitting with his back against the wall in restaurants, walking on the outside of sidewalks to protect me.

“He talked very little about what was happening in Vietnam, but he didn’t need to say anything for me to understand that his life was in danger every day.”

After Bill returned to Vietnam, his letters arrived less frequently, and he soon stopped making the audiotapes. For the last two months, he was completely out of touch.

On April 1, 1969, Bill Morris landed at California’s Oakland International Airport and headed for the nearest pay phone. Seven months had passed since the last time they talked.

“I heard his voice and told myself, ‘Take a deep breath. He’s on American soil,’ ” Sharon says.

A different Bill Morris was on his way home.

Part 4: Agent Orange leaves its mark on the life of Heather Bowser

Unfinished Business: Suffering and sickness in the endless wake of Agent Orange